- FEATURE

- |

- MERGERS & ACQUISITIONS

- |

- FINANCIAL

- |

- MARKETING

- |

- RETAIL

- |

- ESG-SUSTAINABILITY

- |

- LIFESTYLE

- |

-

MORE

After a year marked by brutal market forces and internal reckonings, Kering is reengineering itself for survival—and possibly, reinvention.

By the time 2025 came to a close, Kering stood as one of the few global luxury conglomerates that had not just endured a year of contraction and investor anxiety—but had begun to recalibrate, reshuffle, and lay the groundwork for a new strategic era. The group had reached a cliff edge. And from that precarious point, it began to glow with something the industry hadn’t seen in a while: resilient energy.

While most luxury players were still surfing post-pandemic euphoria in 2023, Kering was among the first to feel the chill. Sales slid, store traffic softened, and Gucci—the group’s flagship and growth engine for much of the past decade—was visibly losing steam. By 2024, its market capitalization had plunged to levels unseen since 2021, and the myth of perpetual luxury growth was beginning to crack. Worse yet, Kering lacked a second-tier brand to absorb the hit. The cracks in the house were no longer cosmetic—they were structural.

In response, the group launched one of the most ambitious internal overhauls in its history, starting with leadership. In June 2025, Kering announced that François-Henri Pinault would step down from his role as CEO, handing the reins to former Renault Group chief executive Luca de Meo. Pinault would transition to a non-executive chairman role, focusing on long-term strategy. The market responded immediately: Kering shares spiked 12.5% the day the news broke, and doubled in value over the following months.

The message was clear. Kering was no longer operating as a family-run fiefdom, but as a corporation prioritizing operating efficiency, asset discipline, and industrial logic. De Meo’s appointment signaled a pivot from creative romanticism to managerial realism.

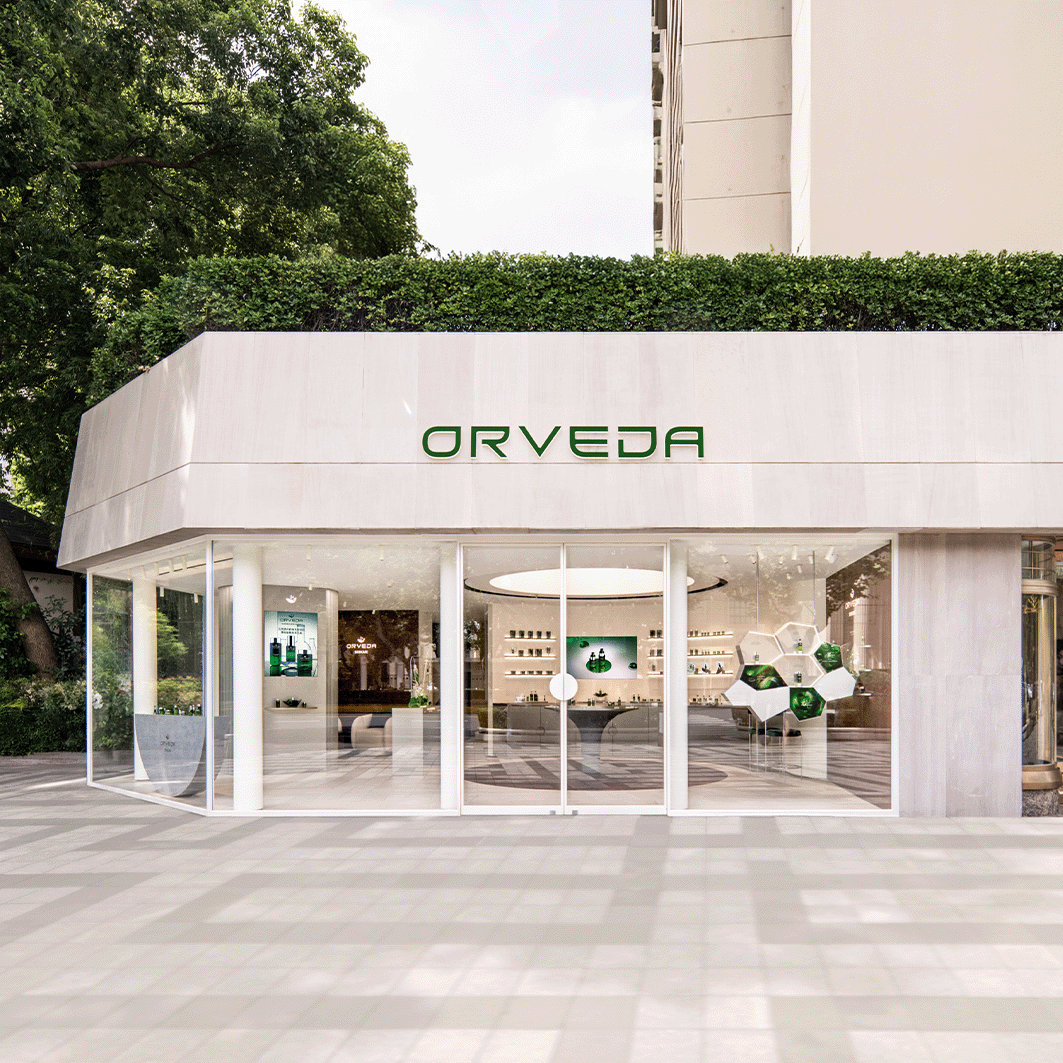

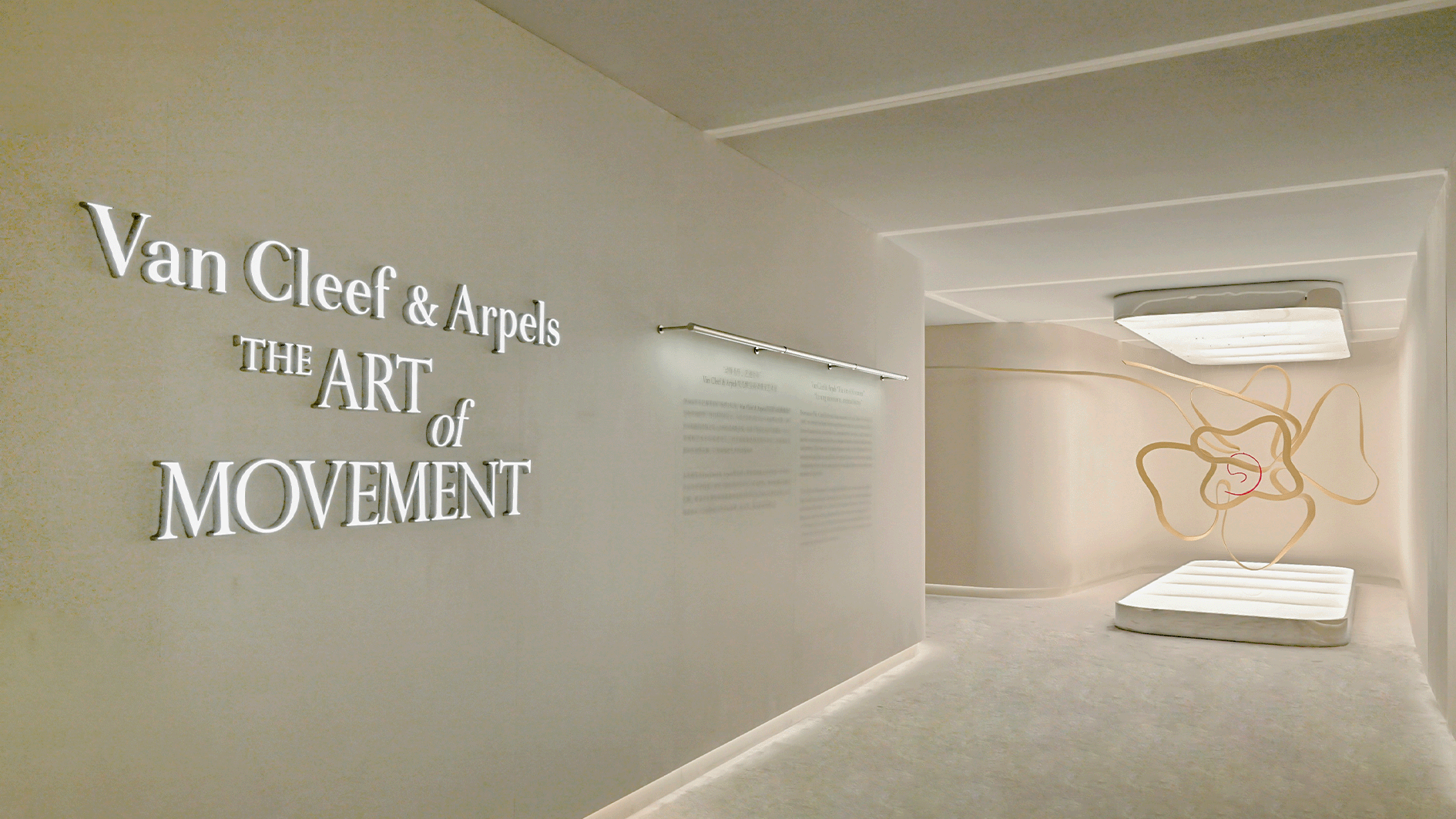

Just one month into his tenure, De Meo made a shock move: selling off Kering Beauté—the newly built in-house beauty division launched only two years prior—to L’Oréal for €4 billion. The sale included not just Creed, the niche fragrance brand Kering had acquired for €3.5 billion, but also exclusive licensing rights for Kering’s fashion brands’ beauty lines for the next 50 years. Post-2028, Gucci’s beauty license would also shift from Coty to L’Oréal. A joint venture between the two giants was also announced, laying the groundwork for potential future collaborations in wellness and luxury segments.

For L’Oréal, this was a windfall. It gained Creed, shored up its existing YSL license, and extended its reach into Bottega Veneta and Balenciaga beauty. If the group’s rumored pursuit of Armani beauty also materializes, L’Oréal would command an unrivaled portfolio in high-end fragrance and cosmetics.

For Kering, the move was more sobering. It parted ways with a business that had shown signs of promise—beauty was one of only two growing categories in its most recent H1 2025 earnings, with Creed delivering a 9% year-on-year increase. But De Meo saw something else: a chance to streamline the balance sheet, shed non-core burdens, and reclaim operational agility. Better to lease brand equity to beauty experts and redirect resources to core fashion categories where Kering had both legacy and know-how.<